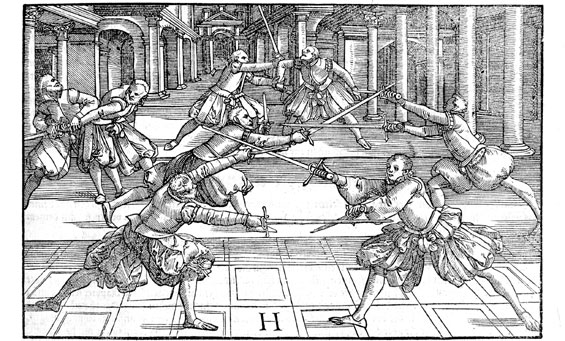

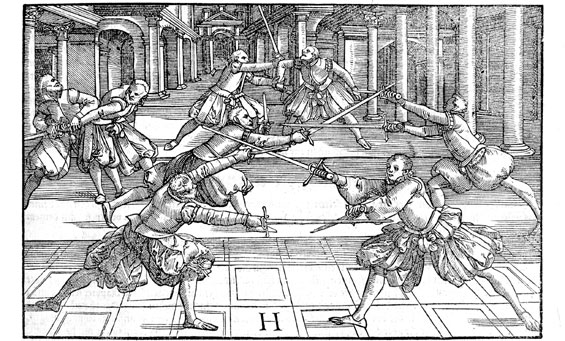

(William R. Short Photo of the Art of Combat (1600) by Joachim Meyer)

ON A RECENT EVENING, a small group of adults dressed in identical black, long-sleeved T-shirts assembled around a table in an airy Worcester basement to pore over an illustration of two Renaissance gentlemen poised to thrust and parry. Nearby, two others stood opposite each other, wielding wooden swords and ready to strike.

''Step with your left foot, in front of his right; cut above to his head," intoned a lithe, bespectacled man, reading from a translation-in-process of a 1,000-page German and Latin manuscript written in 1550 by Paulus Hector Mair, a civil servant and amateur fencing enthusiast from Augsburg, Germany, who was later hanged at age 62 for embezzlement. The man paused, lifted his head, and said, ''Some of the time when he says in front of,' I don't know that he means right in front of, or kind of in the area in front of."

Such is the Talmudic parsing that takes place among members of the Higgins Armory Museum's Sword Guild, which meets every Tuesday evening in the bowels of this imposing 1929 Art Deco pile to revive the lost techniques of European martial arts from cryptic instructions advising knights and other swordsmen how to kill, maim, beat, and sometimes just humiliate their opponents with an arsenal that includes rapier, dagger, dusack, long sword, and falchion.

|

To the motley group who form the guild, the meetings are a chance to feed an obsession with swords and swordsmanship while contributing to serious historical research. During the workday, they are graphic artists, historians of science, mechanical engineers. But after hours they perform demonstrations on the Renaissance fair circuit or take part in Civil War reenactment units like the Salem Zouaves - or decipher nearly impenetrable manuscripts and handpainted and engraved illustrations in order to revive a historic art form that invokes combat, choreography, physics, and, frequently, the muscular application of the Pythagorean theorem.

''People in various ways in their lives are looking for authenticity. They're looking for authentic selves, authentic practices they can really believe in," says Jeffrey Forgeng, a curator at the Higgins Armory Museum who is cofounder of the Sword Guild and a reader at tonight's session. And for him and his brothers (and a few sisters) in arms, nothing satisfies this hunger like translating old manuscript instructions and putting them into action.

. . .

Historical interest in the martial arts of medieval Europe goes back at least to late 19th-century Germany and Britain, though the very real battles of World War I took the lives of many of these early enthusiasts. Thereafter, according to Forgeng, most people who consulted older fight texts did so primarily to find inspiration for stage and film choreography.

Today, the Higgins group is part of a burgeoning movement to translate the often fiendishly difficult texts and make them widely available. Many of the translations are posted on websites of the Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts or the Sword Guild itself or are published by specialty presses like the Texas-based Chivalry Bookshelf. Locally, pockets of students at MIT, the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, and elsewhere are picking up swords and eschewing Society of Creative Anachronism-style whimsy in favor of the smooth (and more historically correct) moves set out by Mair and his ilk.

The Sword Guild was born in 1999, when Forgeng - a former medieval studies graduate student who became interested in historical fighting after hearing a presentation by the choreographer for the television show ''Highlander" - moved to Worcester and joined forces with Patri J. Pugliese, a Harvard-educated historian of science and a lifelong sword enthusiast. (Last month, the Raymond J. Lord Collection of Historical Combat Treatises, a collection seeded by 100 manuscripts amassed by Pugliese and named for the father of another guild member, was dedicated at the Massachusetts Center for Renaissance Studies at UMass-Amherst.)

Forgeng first heard of Pugliese through their mutual interest in Renaissance dancing. According to Forgeng, swordplay and dance have been kindred pursuits since the 16th century, when very often the same person would teach both. ''These were two skills that you would learn as part of your repertoire of accomplishment as a gentleman," he says.

Pugliese, a visiting scholar at MIT's Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology, attributes his love of the sword to his mother, Julia Jones, who in 1929 became the first U.S. intercollegiate fencing champion and worked as a professional coach until her death in 1993.

''I grew up with the idea of the sword," he says. ''We always both knew that she was the master and I was the student, and it was as simple as that. Whenever we had tough times, we decided we would do an hour a day of fencing, and it gave us something together."

But living by the sword isn't always easy, as guild member Jeff Lord can attest. Last summer, after being laid off from his high school teaching jobs in Greenfield and Hadley, he decided to try to support himself entirely through sword-related pursuits. ''There's the tired old cliché, Do what you love; money will come,"' says Lord, who today patches together an income coaching fencing at Amherst and Hampshire colleges, teaching stage combat for middle and high school students, doing fight choreography for high school theater productions, and teaching historical combat at the Higgins Armory. ''Since September, I have actually turned down a number of jobs that were not sword-related, just to be able to look back and see how I did in nothing but swords," he says.

Though the group is careful to stop short of injurious contact, the physical demands of their work are apparent at the study session, as fighters twist their arms and seem to torque their backs unnaturally to conform to the arcane instructions.

Pugliese describes their work as a kind of scientific experiment. ''Your primary material is the early accounts," he says. ''You formulate a hypothesis about what's going on, stand up, take measure of each other, and try to test your hypothesis. Does this work?"

Forgeng seconds the point. ''If there's a sentence that talks about a particular physical maneuver, I can't understand that sentence as a text unless I have a provisional understanding of what it's trying to say physically," he says."There's a dialogue between those two sides."

. . .

The sword guild isn't just about boys and their toys. Female fighters, while rare, can be found in the earliest surviving fight manual, the ''Walpurgis Fechtbuch," which was written primarily in Latin in central Germany roughly 700 years ago. In that manual, a swordswoman named Walpurgis is depicted fighting a male opponent, and references in subsequent texts show women participating in judicial duels against men, Forgeng points out.

In fact, there's nothing in fencing ''that inherently favors the male over the female," Pugliese says. ''It helps to be stronger, but I can find you any number of women who are stronger than I am."

''I can't tell you how many times I've been at events where people say, Well, women didn't use swords,' and here we have evidence just blowing that out of the water," says Holly Hunt, a Shrewsbury resident who is among the Guild's four long-term women members among its 20 regulars. She says that women historically studied fencing to defend themselves.

Hunt, who works in information technology at Worcester's EcoTarium, credits the guild's methodical approach with stripping away the machismo associated with weaponry and replacing it with reverence. ''What we learn in the guild are basically deadly techniques," she explains. ''It gives me a new appreciation of what swords are about. They're not just from Errol Flynn movies; they're personal and violent."

The group's work also sheds light on developments in martial arts practice over time, from subtle changes in index finger positions to broader shifts in the purpose of the fighting.

In the 14th century, says Lord, martial arts practice was a deadly serious and highly elite matter. But by the early 16th century, manuals show a relative lightening up around the proceedings. In a manuscript from 1600 by Joachim Meyer, also from Augsburg, Germany, for example, there are illustrations of a cat, oblivious, licking itself near a duel. Observes Lord, ''It changed from a pure agonistic pursuit to ludic distillation" - in other words, into a more symbolic, and playful, struggle.

While several guild members have done stage choreography, they don't hesitate to point out inaccuracies in Hollywood's version of medieval fighting. Mark Millman, a teacher at the Higgins, points out that the aim of real combatants would have been to kill quickly rather than draw out their battles, as is often seen in the movies. Lord adds that in the recent movie ''Kingdom of Heaven," Godfrey of Ibelin (played by Liam Neeson) makes reference to a two-handed technique called Guard of the Falcon, even though it wasn't introduced until about two centuries after the Crusades.

In the end, the work of the Sword Guild is as much about romance and scholarship as it is about what Forgeng calls ''a process of striving." Trying to imagine and enact what Mair directed his combatants to do centuries ago, he says, ''is a process of self-betterment that improves your German, improves your logic, improves your self-discipline."

Sara Ivry, a writer living in New York, is the associate editor of Nextbook.org.